Automagical Deploys from Docker Hub

I want the speed and other advantages of a static site generator, but with the flexibility of a database-backed CMS.

I want performance, flexibility, and ease of maintenance.

From cars to computers, getting both flexibility and performance all too often requires a carefully weighed set of trade-offs. Generating content for your readers and fans on the web is no exception. On the one hand, techies have recently embraced static site generators such as Jekyll, and for good reason, as these systems provide a lot of advantages (e.g., deploying straight to Github pages, high performance, and ease of keeping your content in version control). However, they are not without their own challenges such as steep learning curves and slow, cumbersome workflows.

On the other hand, flexible, database-backed content management system such as WordPress can be a better choice in some situations. It’s very nice to have the flexibility to allow non-technical people to edit and update content, and for authors to edit online from anywhere without needing a special suite of software and skills. However, CMSs such as WordPress can also be slow, temperamental, and hard to optimize.

Lately, I’ve been trying to find a good balance for my website. Currently, it takes the techie-approved approach: serving static pages via Jekyll. There are lots of things to recommend this approach. I LOVE that people from the community can make pull requests to the site from Github, which has helped me clean it up tremendously. I also value the performance and general ease of maintenance of just serving up static files using Nginx. However, using Jekyll (especially on new computers) can be slow and cumbersome — my stack is based on Octopress and it gives me a lot of heartache due to my noob status in the Ruby ecosystem and because of some not-so-great design decisions I made early on. Additionally, if I merge in a minor change on Github, then I have to fetch the changes to a local computer where Octopress has been set up to perform correctly, re-generate the site using some rake commands and then deploy it again. Not immensely difficult, but not trivial either, and if I am catching small mistakes every day and I want to keep the blog in sync instead of letting it slip, the time to regenerate and re-deploy the site starts to add up quickly. Usually I just let things slip, including keeping the changes up to date on Github.

Additionally, Github’s online markdown editor is nice (and fast), and I wouldn’t mind writing whole articles on there from time to time. If I could write using only Github and deploy on commit, a world of possibilities would open up. Yes there is Github Pages, but if I decide to switch static site generators later on I am hosed (plus, I want to eventually finish migrating to hugo).

Game on.

So what to do? Well, lately I’ve been thinking that I could reduce a lot of pain by chaining together some automation systems and deploying directly from an automated build on Docker Hub by using the great Web Hooks feature. This would allow me to trigger a re-build and re-deploy of the blog whenever there is a change in source control on master, and it would all run asynchronously without needing my attention. Better still, this technique could be applied generally to other stacks and other static site generators, letting anyone roll out a solution that fits their needs no matter what they’re building.

To accomplish this, I did the following:

- Built a

Dockerfileto compile the latest static site from source using our chosen stack (Octopress in my case) - Set up an automated build on Docker Hub which will re-build the image from scratch whenever a change is made on Github (including merges and the online editor)

- Used Docker Hub’s Web Hooks to make a

POSTrequest to a small “hook listener” server running on my Linode which re-deploys the new image (props to cpuguy83 for helping me with this)

Step 1: Build a Dockerfile for our static site generator

This is my Dockerfile for this Octopress build, it installs dependencies and then creates the site itself:

Apparently, Jekyll has a Node.js dependency these days. Who knew? (Side note: Writing my Dockerfiles in all lowercase like this makes me feel like e e cummings. A really geeky e e cummings.)

This Dockerfile is really cool because the bundle install gets cached as long as the Gemfile doesn’t get changed. So, the only part that takes a non-trivial amount of time during the docker build of the image is the rake generate command that spits out the final static site, so the whole process runs quite quickly (unfortunately, though, Highland, Docker’s automated build robot, doesn’t cache builds).

I would love to see some more of these for various static site generating stacks, and I intend to contribute just a vanilla Octopress / Jekyll one at some point soon.

Octopress is pretty finicky about only working with Ruby 1.9.3, so I was fortunate to be able to find a Debian package that fulfills those requirements. The static files get served up with nginx on port 80 of the container (which I just proxy to the host for now), which works well enough for my purposes. In fact, I just have all the gzip and other per-site (caching headers etc.) settings in the nginx config in the container, so I can deploy that stuff this way too (just change the source in the repo and push to Github!). I like this kind of high-level-ops knowledge PaaS fusion mutated weirdness. Yum.

This approach cuts my “native” sites-available file for the websites down to something like:

The hubhook is some proxy-matic goodness, which farms out the task to re-deploy the site to a simple but effective “Docker Hub Listener” worker that my colleague Brian Goff originally wrote (and which I twisted to my own nefarious purposes, muahaha). Okay, on to the next steps.

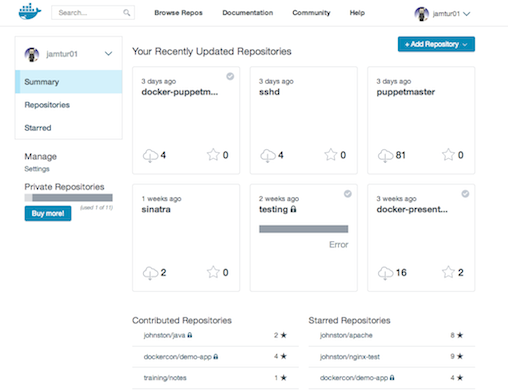

Step 2: Set up Automated Build for this repo on Docker Hub

This step is crucial, and really illustrates the power and flexibility of Hub’s automated builds (which if you haven’t tried them already, you totally should). When a change (commit, merge or otherwise) hits the dockerize branch on Github (though it could be any branch, and eventually it will be master for me), it triggers a re-build of the images with the most up-to-date Dockerfile. This means that new articles I have written or content that I have added will be re-built asynchronously by Highland without needing any attention from me. So, even if I merge in a small revision from another user on Github or make a quick edit with the online editor, the site will be rebuilt from source (which is mostly Markdown files and a “theme” template). Note that automated builds work with Bitbucket too if you prefer Bitbucket!!

And, critically, this method takes advantage of a powerful Docker Hub feature called Web Hooks which allows you to make a POST request to the endpoint of your choice whenever a new build is complete. This is what I use to re-deploy the website.

Step 3: Post to the hook listener server and re-deploy!

I had been kicking around the idea of implementing something like this for a while, but I was missing a piece. I had no server to listen for the request from Docker Hub when the build was completed. Then, serendipitously, my colleague Brian Goff (also known as super-helpful community member cpuguy83) demoed a “webhook listener” that was the very thing I was thinking of writing myself (only his was better thought out, to be be honest). It’s a tiny little Golang program which allows you to register handlers that run when the hook hits, and which has support for both self-signed SSL (so you can send the request with encryption / https from Docker Hub) and for API keys (so that even if black-hats know the endpoint to hit, they won’t know the API key to pass to actually get it to do anything).

Link to the repo here:

To get it to work, I generated an OpenSSL key and cert (which I linked to in a config.ini file passed to Brian’s server program).

I wrote this script to automate that key/cert generation:

Then I generated a random API key and also added it to the config file. So, in the end, the config.ini file that I use lives in the same directory as the dockerhub-webhook-listener binary and it looks like this:

Lastly, I wrote a simple shell script to run whenever the hub hook listener received a valid request, and wrote a Go handler to invoke it from Brian’s server program.

The shell script looks like this:

Just keeping it simple for now.

The Go code looks like this:

func reloadHandler(msg HubMessage) {

log.Println("received message to reload ...")

out, err := exec.Command("../reload.sh").Output()

if err != nil {

log.Println("ERROR EXECUTING COMMAND IN RELOAD HANDLER!!")

log.Println(err)

return

}

log.Println("output of reload.sh is", string(out))

}

As you can see, there’s nothing too fancy here. It’s just Plain Old Golang and Shell Script. In fact, it could be a lot more sophisticated, but this works just fine- which is part of what pleases me a lot about this setup.

Finally, we use the Docker Hub webhooks configuration to make the POST request to the endpoint exposed on the public Internet by this middleware server. In my case, I added an endpoint called /hubhook to my nginx configuration that proxies the outside request to the dockerhub-webhook-listener running on localhost:3000. The API key is passed as a query string parameter, i.e., the request is to /hubhook?apikey=bigLongRandomApiKeyString.

So, pieced together, this is how this all works:

- Commit hits Github

- Docker Hub builds image

- Docker Hub hits middleware server with hook

- Server pulls image, and restarts the server

Automagical.

Now my deploys are launched seamlessly from source control push. I really enjoy this. Now that everything is set up, it will work smoothly without needing any manual intervention from me (though I need additional logging and monitoring around the systems involved to ensure their uptime and successful operation, in particular,& the hub hook listener – oh god, am I slowly turning into a sysadmin? NAH)

There is still a lot of room for improvement in this setup (specifically around how Docker images get moved around and the ability to extract build artifacts from them, both of which should improve in the future), but I hope I have stimulated your imagination with this setup. I really envision the future of application portability as being able to work and edit apps anywhere, without needing your hand-crafted pet environment, and being able to rapidly deploy them without having to painstakingly sit through every step of the process yourself.

So go forth and create cool (Dockerized) stuff!

nathan leclaire

nathan leclaire