Prompt Engineering to Grow Yourself a Nanoservice Garden

About a year ago, riding high on my first access to gpt-4-32k, I cobbled together a project that embodied a vision I’d been dreaming on: what if software engineering evolved into a kind of “DJ-ing” with natural language instead of clunky code? Could we usher in the next million creators of “bicycles for the mind”? I imagined a world where everyone could nurture their own garden of software, conjuring up bits and pieces to remix with others' creations. (Devin wasn’t around then, but it seems to be inching towards this idea, albeit via a different route.)

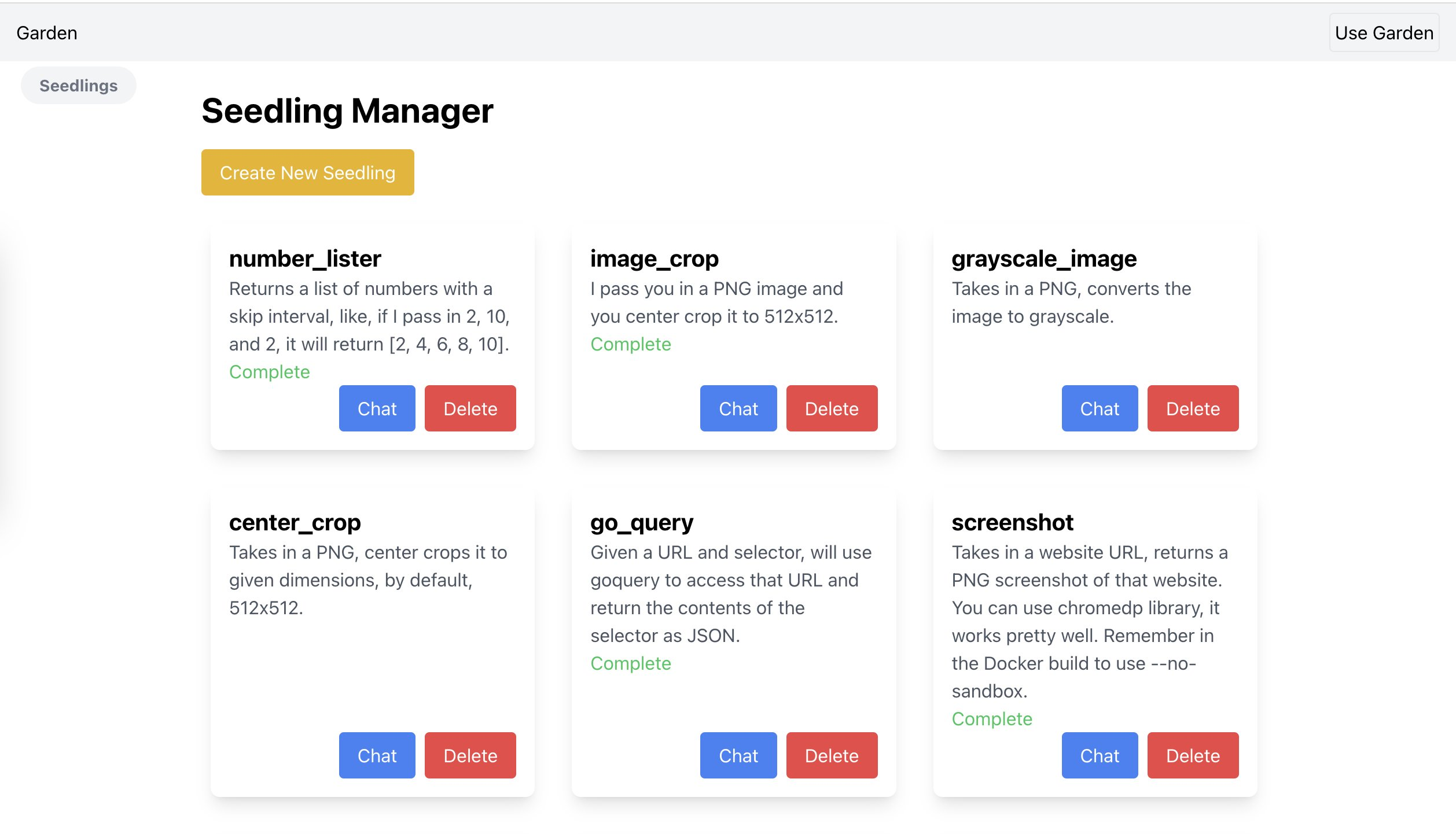

I, with a bit of inspiration and feedback from friend Lucas Negritto, built out a prototype that would take your input, and create a working gRPC service for you! I called it GARDEN — with accompanying obnoxious AI generated backronym, GPT Assisted Robust Development of Nanoservices. Code is up on Github here if you want to go check it out.

The project involved a fair bit of prompt engineering and chaining various outputs and concepts together. I had a fair bit less hands on experience with LLMs then than I do now, so I thought it would be an interesting exercise to look back on it and reflect on where the prompting and approach was good, and where it could be better.

The Project

The Garden project focused on key aspects of software development: well-defined schemas, robust clients, consistent environments, and portable, composable apps. Drawing from my times at Docker, of course I saw everything through the lens of running in Linux containers. The design followed a step-by-step approach.

- First, the AI would help generate a gRPC/protobuf definition for how you would access the service, i.e., the methods it supports. This would assist a lot in setting up boilerplate code (since it can be generated), enabling eventually services in a wide variety of languages out of the box, and . It would provide a “schema” to work with that could be transposed pretty directly to HTTP.

- Then, the boilerplate for the service would be generated with the gRPC compiler.

- The AI would then be prompted to actually implement the service, using whatever libraries, etc., it desires.

- The AI would then prompted to write the Dockerfile for the implementation, which of course includes building and compiling it, etc.

- If needed due to errors, the program would report the error and try to get the issue fixed, similar to how Code Interpreter will try multiple times if it hits an exception.

Then, it would go actually start the thing, which I would usually test out with curl. Along the way, each step’s results would be tracked in a git repo.

Let’s take a look at decomposing this process and the various bits of prompt engineering I used, and what I would likely do differently these days with the benefit of experience.

Thinking Step by Step

It’s well known that using Chain of Thought techniques (the simplest of which is just to tell the model, “Think step by step”) can enhance model performance. (see: Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners). To that extent, having things broken out as I did into several “steps” was a good start.

Paraphrasing the code, the core logic in the “agent” that develops a “Seedling” (service) is along these lines:

func gptThread(seedling Seedling) {

ctx := context.Background()

c := llm.NewClient(os.Getenv("API_KEY"))

steps := []string{

SeedlingStepProtobufs,

SeedlingStepServer,

SeedlingStepDockerfile,

SeedlingStepExampleClientCall,

SeedlingStepComplete,

}

step := findStartStep(steps, seedling.Step)

for runs := 0; runs < maxRuns; runs++ {

for {

if steps[step] == SeedlingStepComplete {

// if everything compiles, we have our service!

// run it and we finish up

launchDockerContainer(seedling.Name)

break

}

// Otherwise, we continue iterating on our prompt based on which

// step it is.

repoPath, codeType, cmdCmd, cmdArgs := getStepConfig(

steps[step], seedling.Name,

)

prompt := buildPrompt(steps[step], seedling, errMode)

gptOutput, err := completion(ctx, c, prompt, calculateTemperature(errs))

if err != nil {

logrus.WithError(err).Error("failed to get gpt output")

return

}

output, err := runSeedling(ctx, buildFilePath(seedling.Name, repoPath), codeType, buildCommand(cmdCmd, cmdArgs), gptOutput, steps[step], prompt, seedling.Description, c)

if err != nil {

// If the program, e.g., did not compile, we feed the error back

// to the LLM, and try again!

handleError(err, output, &prompt, &errMode, &errs)

if errs > maxErrs {

step = findStartStep(steps, seedling.Step)

break

}

} else {

updateSeedlingStep(ctx, seedling.ID, steps[step+1])

prompt = updatePromptForSuccess(prompt, gptOutput)

step++

}

}

}

}Let’s break down the steps and their individual prompts and logic to see what seemed good, and what could be improved.

Protobufs Step

gRPC services (defined using protobufs) have a variety of appeals, in our case, namely easy code generation and standardization of services.

For this step, we construct the prompt like so:

if !errMode {

prompt = fmt.Sprintf("%s\n", fmt.Sprintf(

protoPrompt,

seedling.Description,

seedling.Name,

seedling.Name,

seedling.Description,

))

} else {

errMode = false

}

prompt += "```protobuf\n"

repoPath = filepath.Join("protobufs", seedling.Name+".proto")

codeType = "proto"

cmdCmd = "protoc"

cmdArgs = []string{

"-I=.",

"--go_out=.",

"--go-grpc_out=.",

repoPath,

}The protoPrompt looks like this:

Write me a protobufs file for a gRPC method that %s

Make sure to start it with lines like:

syntax = "proto3";

option go_package = "./protobufs";

The file will be called %s.proto. Do not override any of my file names.

My directory layout is:

$ ls .

Dockerfile client docker-compose.yaml go.mod protobufs server

My go.mod is:

module %s

go 1.22

There are some arguments and variations that a user will be likely to request.

Make sure to include them. Think about it like a product manager for a developer experience

-- what are people likely to want from a service that does %s?

This is the initial request to the system to create the “schema” for the service.

It’s relatively simple and constrained, which is good — a lot of prompts I see flying around for LLMs are far too verbose! And the poor things get pulled in too many directions. (See: Be clear, direct, and detailed).

I used the older Completions API instead of Chat in this project. This probably isn’t ideal, as models perform better when they can “think out loud.” I asked for a single Markdown code block, but LLMs prefer to respond as if they’re chatting or writing an article. A better approach might’ve been to use Chat completions and parse the reply starting from the triple backticks. That said, the models often think through comments anyway, so maybe it’s fine. At any rate, the usage here is reminiscent of prefilling responses.

Think about it like a product manager for a developer experience -- what are people likely to want from a service that does %s?, I think, it a good bit of prodding. It tells some context, including who this is more or less for, and was really useful in getting the thing to go a bit above and beyond adding various config options and ergonomics to the definitions, rather than just fulfilling the bare minimum of what the prompt would ask for. The contextual information about the directory structure really helped a lot to get something that would compile on the first try.

Once that service definition was generated, it would be committed to a git repo, then we would move on to adding the next step.

These days, if I was using Claude, I would definitely delineate various sections with their XML tags, like:

<directory>

$ ls .

main.go go.mod

</directory

Those help the model to chunk out the various pieces of the request.

Server Step

Then we would actually ask the LLM to go implement the thing. This was the trickiest step to get working and in my opinion looking back, partially that was because the prompt and step was trying to do too much at once. Let’s take a look at the prompting.

If all went according to task, the following whopper of a prompt would get thrown at the LLM! Take note of the %s at the very beginning — that’s an important bit of how the whole flow worked together because, in “non error” mode (first attempt), it would be empty, but it would be the basis for chained previous results (to try and get the LLM to fix any mistakes).

fmt.Sprintf(`%s

Now write a server implementation for the service method(s).

It should be package main.

Here are some instructions:

1. Make sure it's an actual production implementation of the service. Implement

everything. Don't leave anything out.

2. Use external libraries, packages, and binaries if needed.

3. Assume you are running in a Docker container (Linux). This will

run on Debian, so make sure it's compatible with Debian (Bookworm).

This should be oriented at processor architecture %s.

4. Make the gRPC service listen on port 8000, with insecure connection

settings. In the same file, also include an HTTP server that will listen on

port 8001, take in JSON equivalent to the gRPC call, and call the equivalent

gRPC server method. If the HTTP server method receives file(s), use FormFile.

5. Log information about each request to the HTTP server with logrus. Use logrus.WithField

to include information about the request, including relevant args, method name, duration etc.

6. Make sure to go the gRPC Serve() in a goroutine, and then block on the HTTP server.

7. In addition to exposing the gRPC service, also expose an HTTP health check endpoint at /healthz.

8. Add an additional HTTP endpoint /schema that will return the schema for the

service, i.e., a JSON representation of the request/response and their JSON

fields, with some extra "labels": [], that describe things like file_type if

there is an arg of []byte. Like, "labels": [["file_type", "image/png"]]. This

will be used to generate frontend code automatically.

9. Don't worry about importing protoimpl, github.com/golang/protobuf stuff. You

don't need that.

Here are example responses from the /schema endpoint:

1.

{

"title": "A registration form",

"description": "A simple form example.",

"type": "object",

"required": [

"firstName",

"lastName"

],

"properties": {

<omitted for brevity>

}

}

2.

{

"title": "Files",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

<omitted for brevity>

}

}

Think step by step. If you want to provide commentary, do it in comments.

Actually implement everything as if it were production ready. Make sure to

terminate all string literals.

Some of the generated protobuf code looks like this:

%s

And the gRPC:

%s

Now let's write the code. Write only the code.This prompt has good elements but overreaches. It tries to create a gRPC service and an HTTP service in one go, which is too ambitious. It should be split into at least two separate prompts, with one focused on gRPC elements, and another on HTTP elements. Surprisingly, it often worked, showcasing the power of advanced LLMs, unlike smaller models like Mistral which would struggle with this complexity.

But ignoring that, let’s analyze it.

It’s really specific, which is good. You can hear my frustration coming through somewhat in terms of the fact that the results I was getting would experience a lot of the “laziness” problem — /* implement service here */ would not be uncommon to see in the output. But many of the other instructions are super specific and assist a lot.

It’s loaded with context. I had strong opinions on how these should evolve – specific ports for host forwarding, standardized logging with logrus, leveraging external packages, file inputs, that kind of thing.

That generated protobuf code bit is pretty critical. By injecting the previous step’s output, we’re basically saying, “Hey, build on this.” It’s much, much more effective for the LLM than having it try to guess the structs and methods right.

In later iterations, I got fancier. The system would automatically look up docs for referenced libraries and inject them. This was clutch when the LLM had a hunch about a useful tool but wasn’t quite nailing the implementation. However, it also ended up polluting the context a lot, because docs could be pretty low signal/noise. The idea needs iterating on.

nonStdImports := getNonStdImports(serverFile)

allDocs := "\nHere is some documentation that might be useful:\n"

for _, imp := range nonStdImports {

cmd := exec.Command("sh", "-c", "go get ./... && go doc -short "+imp)

cmd.Dir = filepath.Join("repos", "default", seedling.Name)

out, _ := cmd.CombinedOutput()

allDocs += string(out)

}

prompt += allDocs

Few shots! (e.g., Use multishot prompting to guide Claude’s behavior) The few shot examples for the schema output worked super well! That helped guide the LLM dramatically in the right direction for what the HTTP /schema endpoint should output.

Ultimately, this step had a lot of good foundational material, and just fell short on the fact that it likely should have been broken out into two, or three distinct steps instead, perhaps building on top of each other. Mixing up all the gRPC and HTTP stuff violated the principle of having one clear result for the LLM to strive for.

What about errors?

Usually this step would be where things would get hairy, and the code wouldn’t always compile. In fact, it quite frequently would not. But at any step, the test to see if the “agent” should progress to the next stage could fail. So each step would have a graduation mechanism, to evaluate if it should move on or not, and if it returned an error, it would try again, while incorporating feedback from the step (e.g., error messages from the compiler) into the prompt again.

One key thing that I do think went well here is that these instructions end up being at the end of the prompt, with all of the context dumped out above. Claude’s documentation recommends to Put longform data at the top, and I bet that having these instructions last, rather than before all the prior messages, helped.

Queries at the end can improve response quality by up to 30% in tests, especially with complex, multi-document inputs.

!

prompt += llmOutput + "```\n\nThat code didn't work.\n\nIt got an error:\n\n```\n" + output + "```"

prompt += "\n\nWrite a version that fixes that error.\n"

errMode = true

If in “error mode”, it would keep thrashing like that until a certain threshold of max retries was reached, and it was somewhat surprising how the system would often converge after two or three tries just by feeding back its own issues.

Nowadays, if i were using Claude, given the XML tags thing I would probably separate things out that way, more semantically, rich, this type of thing:

This is the protobufs file.

<proto_file>

%s

</proto_file>

And the generated Go code.

<generated_code>

%s

</generated_code>

Write the definition for the service.

<attempt>

%s

</attempt>

Sorry, that attempt failed with errors.

<error_output>

%s

</error_output>Quality Checking

However, laziness was a huge problem. The code would get to a state where it compiled, but the LLM would cheat by inserting // Implement this here type of comments instead of actually doing something useful. One of the more novel ideas we came up with and implemented to fix this was to pit the LLM against itself by doing a new LLM call to look at its generated code in a “quality check”. This would then evaluate if the program implemented the request as planned, returning a structured output, which then could be fed back into the original prompt chain, to assist with ensuring the responses were quality.

type QualityCheck struct {

Quality string `json:"quality"`

Reason string `json:"reason"`

Suggestions string `json:"suggestions"`

}

func (qc QualityCheck) Error() error {

if qc.Quality == "good" {

return nil

}

return errors.New("Quality check failed for this reason: " + qc.Reason + ". To improve the quality, we suggest you: " + qc.Suggestions)

}

qualityPrompt := fmt.Sprintf("```\n%s\b```"+`

In the above code, based on how well it seems to implement the desired

functionality of a service that %s, output JSON with this format:

`+"```"+`

{"quality": "good", "reason": "would definitely pass a code review", "suggestions": "none"}

{"quality": "bad", "reason": "unimplemented method", "suggestions": "actually implement the functionality"}

`+"```"+`

The quality check should return "bad" if there are TODOs, stubs, methods,

examples, simulations etc. that just return nil or true without doing anything,

etc. For instance, "we'll do this later" is a strong indication that the code

quality is "bad".

`+"```json\n", gptOut, description)

qualityCheckOut, err := completion(ctx, c, qualityPrompt, 1.0)

if err != nil {

logrus.WithField("error", err).Error("failed to get gpt output")

return "", err

}

qualityCheckOut = strings.TrimSpace(qualityCheckOut)

var qualityCheck QualityCheck

if err := json.Unmarshal([]byte(qualityCheckOut), &qualityCheck); err != nil {

logrus.WithField("error", err).Error("failed to unmarshal quality check")

errs++

continue

}

if qualityCheck.Quality != "good" {

prompt += "```" + fmt.Sprintf(`

You didn't pass the quality check. Here's the output from the quality check:

%s`, qualityCheckOut)

prompt += "\n\nWrite a version that fixes that error.\n"

return "", qualityCheck.Error()

}In my opinion this worked quite well, and enabled a hybrid approach that would have some “fresh” LLM calls without too much mucking up the context, to get some new energy into the ongoing, vastly expanding context of the main prompt.

Dockerfile Step

Once the service itself was written and quality checked, we presumably had something worth moving foward with. Just one issue. I told the LLM that it could use dependencies, such as imagemagick or ffmpeg, at will. We need a consistent environment to run these in. (It would be very useful indeed to be able to share seedlings around on all of your computers or with your friends!) Docker, of course, is our answer here. We have yet another step growing what is at this point, our relatively massive core prompt.

prompt = fmt.Sprintf(`%s

Now write a Dockerfile (multi-stage build) to build and run your server.

Here is an example:

FROM debian:bookworm-slim AS builder

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends \

ca-certificates \

git \

golang-go \

<other_pkgs>

COPY . /app

WORKDIR /app

RUN go get ./...

RUN go build -o /tmp/svc ./server

FROM debian:bookworm-slim

RUN apt-get update && apt-get install -y --no-install-recommends \

<package_1> \

<package_2>

RUN groupadd -r appuser && useradd -r -g appuser appuser

COPY --from=builder /tmp/svc /bin/svc

RUN chown appuser:appuser /bin/svc

USER appuser

EXPOSE 8000

EXPOSE 8001

CMD ["/bin/svc"]

Make sure to install any external libraries, packages, and binaries you need.

Make sure to include this line:

RUN go get ./...

Think step by step -- what's the best way to build the file?

Write the code. Write only the code.

`, prompt)That Dockerfile is begging for <dockerfile></dockerfile> tags, for starters. The key here is giving it a super specific example to mimic. Sure, it could often spit out a decent Dockerfile without that, but it rarely hit the mark for our peculiar port forwarding needs and whatnot. Looking back, having it write the whole shebang seems a bit much. I was aiming for flexibility to handle various languages and runtimes, but we probably should’ve zeroed in more. Might have been smarter to just ask for a specific list of Debian packages to toss in.

Magic cheese lines Think step by step and Write only the code seem, fine? But I’m not sure how much they really add these days. It probably would have been better off specifying why and what is desired in that thinking and what the goal is here — is it consistent operation? Is it a creative environment for the dependencies to thrive?

Remember, each intermediate bit of generated code that works is committed into a git repo, so — once this was solid, it was checked in as Dockerfile and we moved on.

Example Client Call Step

Miraculously, this would all work reliably-ish (well, compile at least — fulfilling the actual request for the service itself was a mixed bag). But then I had a service I wanted to test out, yet I would be digging through its generated code and trying to put together the commands to actually use it by hand. That wasn’t super fun, so I also added a step to generate a client to test them —

prompt = fmt.Sprintf(`%s

Now write me a shell script with a example client call with curl to the HTTP

service. which is running on localhost:$(docker inspect -f '{{ (index .NetworkSettings.Ports "8001/tcp" 0).HostPort }}' %s).

If it needs an input file or multiple input files, pass those in as args. If

this is true and the args aren't present, error out.

In the script, set:

`+"```"+`

set -euxo pipefail

`+"```"+`

Remember, the server code is:

`+"```go\n%s```", prompt, seedling.Name, serverContents)The exact port specification is a clever touch. It’s like giving the LLM a precise thing to conform to, keeping it from inventing arbitrary SERVICE_ENDPOINT variables. This consistency in naming and I/O is super helpful for reproducible results with LLMs, which is why I thought protobufs were so promising.

Of course, we tell the LLM to use the One True Set of Bash Script Options. The actual results were just OK. Simple services like “add two numbers” usually worked fine, but complex stuff like image file inputs got finicky (though we did manage to crop images!). The prompt needs more work to consistently produce great clients – probably with a fresh context rather than dumping the whole thread. Still, it beats manually fiddling with cURL.

We also could probably get this to perform better by, once again, flipping the order of request and context. So something more like:

<server_code>

%s

</server_code>

Now write me a shell script with a example client call with curl to the HTTP

service, which is running on

<endpoint>

localhost:$(docker inspect -f '{{ (index .NetworkSettings.Ports "8001/tcp" 0).HostPort }}' %s).

</endpoint>

If it needs an input file or multiple input files, pass those in as args. If

this is true and the args aren't present, error out.

In the script, set `set -euxo pipefail`.In fact, this would be a perfect case for prefilling in chat context. This type of thing:

{"user": "<server_code>...</server_code> Now ... "}

{"assistant": "Yes, let's write a script. ```#!/bin/bash\nset -euxo pipefail\n"}Results

It was kind of trying to do too much, but I’d say that the basic ideas were successful enough that it’s a direction worth continuing in! In particular, I’d split things out and make more sophisticated chains, and of course, get in more useful context! Context, context, context — there’s never enough detail, although it’s always a fine line between polluting the prompt too much, causing the AI to fall apart and get stuck in error loops or lose focus, and providing more details.

Anyway, I hope that’s a helpful reflection on prompt engineering, and you learned a few things. Now, can somebody just go and make GARDEN right so I can use it? Thanks and stay sassy Internet.

- N

nathan leclaire

nathan leclaire