Do We Need a New Orchestration System for GPUs?

Lately, I’ve been working on Tensorscale, which was born out of my frustration with not being able to access my perfectly good GPU while working elsewhere on Stable Diffusion projects. Even if I was just sitting on my couch, the problem remained the same. Gradio public sharing or ngrok were potential solutions that could have allowed me to access the automatic1111 web UI, but they had some issues for my use cases.

For instance, I wanted to be able to build a web app that could handle Stable Diffusion tasks like image rendering and training using my home GPU, without going through a networking layer that wasn’t really designed for it like Tailscale or whatever. Using an AWS server for small projects is too expensive, costing at least $1k per month if kept on constantly. Even the cheapest providers want like $0.60 per hour. The idea of hackers being able to deploy a web app on a $5 per month server and remotely accessing their hardware was fascinating.

I was also interested in automation and programmability. Although auto111 offers an excellent imperative interface for completing tasks, most of the work in Stable Diffusion involves pipelining model results together and managing minor details like prompts, inpainted images, and dimensions. You tend to end up fiddling with settings, and waiting, waiting, waiting, when it’d be nice to just throw some stuff into a big pile.

So I had this idea to make a system where you could run stuff on your own GPU at home, or across clouds or whatever. A few product interviews with AI companies showed me that everyone was reinventing the wheel when it comes to this stuff. Spending time on an unreliable AI system was hurting people’s ability to create cool products or differentiate themselves, such as by making custom models. So, I pulled on the thread.

I want to preface this by saying that I’ve been working on and thinking about this mostly in isolation. Therefore, I welcome feedback on where I may be wrong or what I might have overlooked. I don’t claim to have all the answers; my intuition and thoughts have certainly led me down many foolish paths in the past.

The needs

When working on AI projects, people want quick, cheap results that are “good enough” for their customers. But, as always, there are a lot of tradeoffs to consider even with the promises of things like serverless GPU providers. In cloud infrastructure, Docker hit a sweet spot between gluing everything together on IaaS and having everything managed for you on PaaS. With increasingly complex technology stacks, one PaaS entity cannot satisfy every need cost-effectively, so it was inevitably that something in the middle would be needed.

Specialized hardware like GPUs present unique challenges in terms of management and provisioning, i.e., they break the fuck out of our existing abstractions and businesses. Cloud providers are between a rock and a hard place as customers need massive burst capacity for GPU workloads, but slicing those isn’t nearly as efficient business-wise as having a massive computer with many virtual machines because of the specialized hardware. If no one wants it at a given time, the damn GPU sits there and collects dust, and even if they do, they’re going to be obsolete in 18 months or so. Yay, more capex.

On the deployment/app side, things aren’t really any easier. Slicing of GPU resources up for concurrent use is hard. Multiple apps may contend for the GPU, leading to inefficiencies or VRAM blowups. Local queue/locking type of systems can be implemented, but this creates unpredictability in latency and elsewhere. Another option is to reserve resources at the device level and use a monolithic service to handle all model needs. But now you’ve taken an infrastructure problem and mashed it up with all your app problems, in a language that isn’t particularly efficient or good at concurrency no less.

Kubernetes abstractions kind of break down due to this. The trade offs are all kind of rough: due to its generalized nature, it can be relatively slow at scheduling (which is bad), over-allocate resources to a single app and offload scheduling complexity to the app (also bad), or force you to deviate from usual system promises about repeatability. e.g.:

As an administrator, you have to install GPU drivers from the corresponding hardware vendor on the nodes and run the corresponding device plugin from the GPU vendor.

FUCK! Weren’t containers supposed to make everything repeatable? I don’t want to do **administration.** That sounds boring and painful. Hopefully Ben will save us all with Replicate.

Anyway, people need alternatives or answers. In the current AI product race, many are building hundreds of (presumably) poor versions of the same thing to solve these problems simultaneously.

In addition to simply solving these general problems, people have developed a lot of flair on top of vanilla inference that they need a system to address.

- They may opt to offload certain tasks to the CPU instead of the GPU if the processing power is available and not being utilized, or if it’s not urgent.

- They have custom models (e.g., Dreambooth) that need to be swapped out efficiently and distributed throughout the cluster.

- They want to deliver results to users requesting inference as quickly as possible, even if it’s just a preview or a stream.

- They want to support interruptibility, as it can be costly to let the AI continue if it goes off on a tangent or is starting to produce a deformed output.

- Different inferences have varying priority levels in terms of when they need to be executed. For example, perhaps free user inferences should only run once paying customer inferences have been completed, or maybe a batch job for training should be killed if demand for instant inferences starts to ramp up.

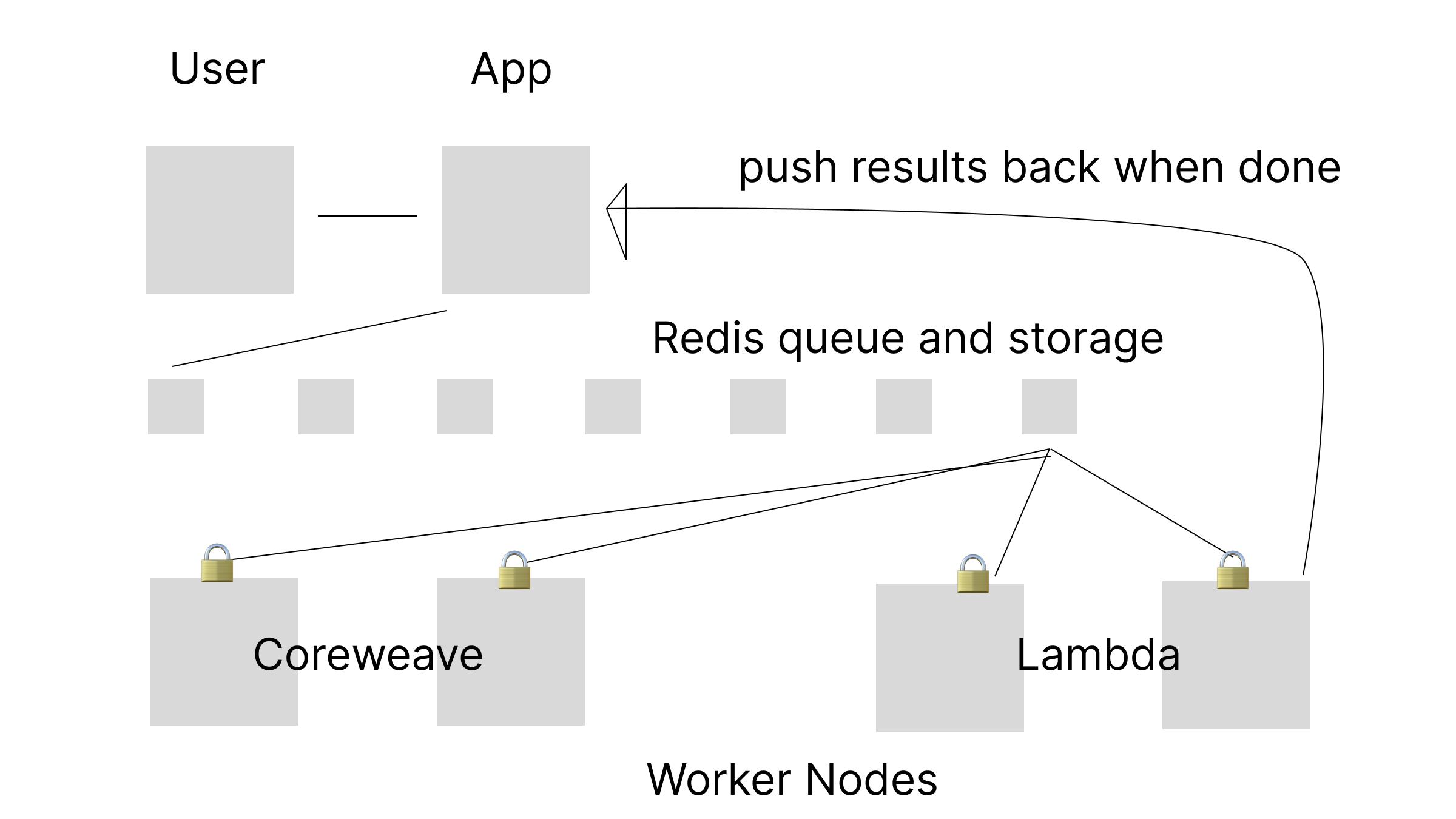

What Most People (Probably) Have

One common way for programmers to distribute AI work across a cluster is to use Redis or something for locking and as a queue. While this approach is cute and clever initially, it can create operational problems down the line. For a more nuanced perspective, see Tef’s blog. In practice, you may find that the queue doesn’t solve all the distributed system problems you face:

- What happens if a node goes rogue or fails?

- What if the queue becomes backed up?

- How do you report errors back upstream?

- How do you communicate intermediate results?

- What if a particular type of workload can only run on a subset of your nodes?

Many of these problems can be solved by systems like Kubernetes, but as we mentioned before, Kubernetes has issues with AI workloads.

These problems are exacerbated by the bursty nature of AI workloads and the competition for GPUs across multiple clouds. Congratulations, you now have networking, secrets, and service discovery issues.

So how can we best support these needs?

A Vision for New Orchestration

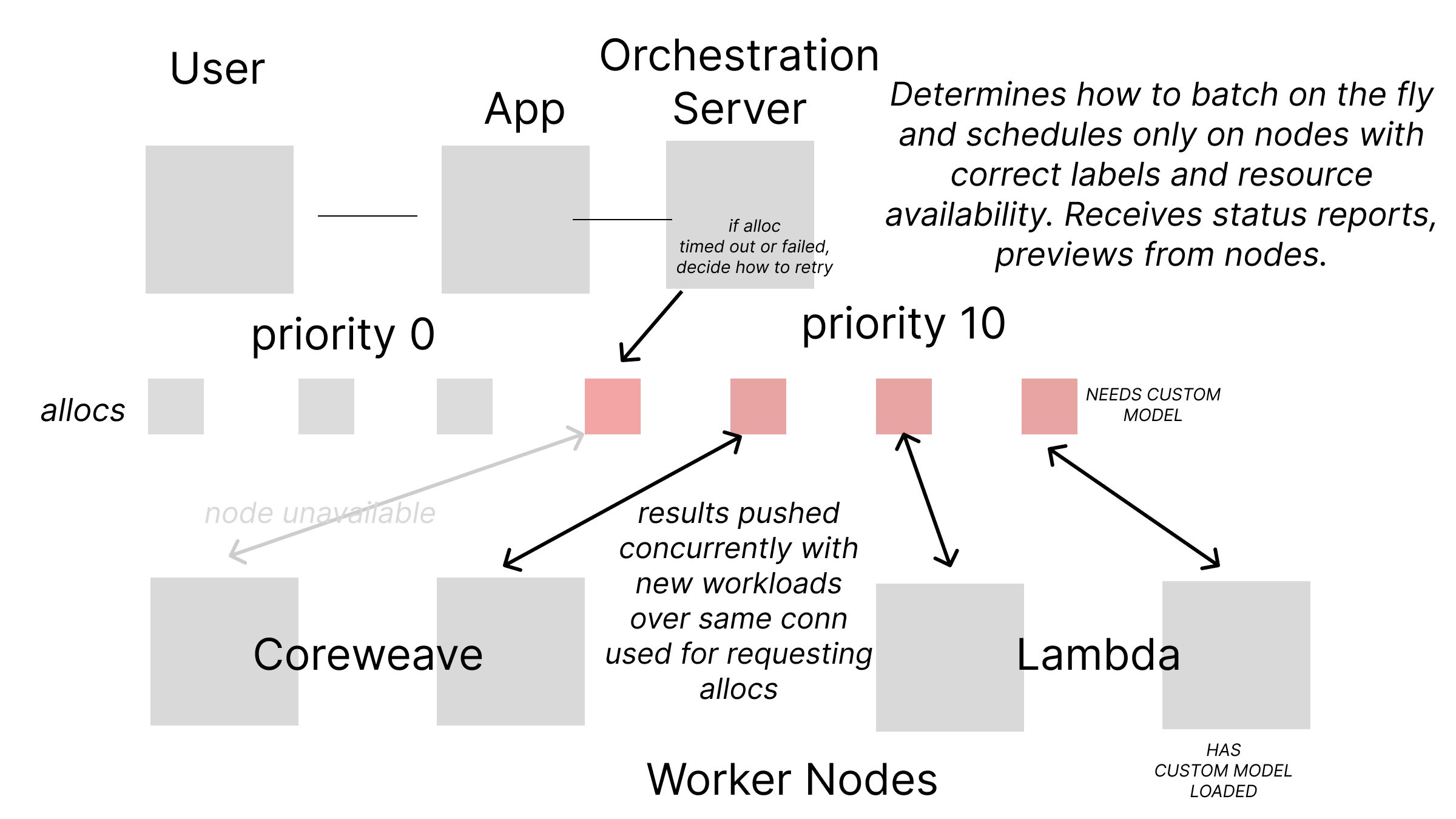

I call this experimental orchestration system “Amostra,” which is the Portuguese word for “sample.” I think of most of its functions as coordinating the sampling of some space, latent or otherwise. The workers also have a few features for pushing telemetry data, so I’m crisscrossing all types of meanings associated with sampling to confuse things. Anyway, the point is that I call it “Amostra.”

The main concept is to establish a two-way connection between a central server and an agent on each node. Similar to how Kubernetes operates with its API server and kubelet, but with the big difference that the agent is currently simple and does not handle tasks like image pulling or networking. (Maybe to address those needs, you could glue it together with cog)

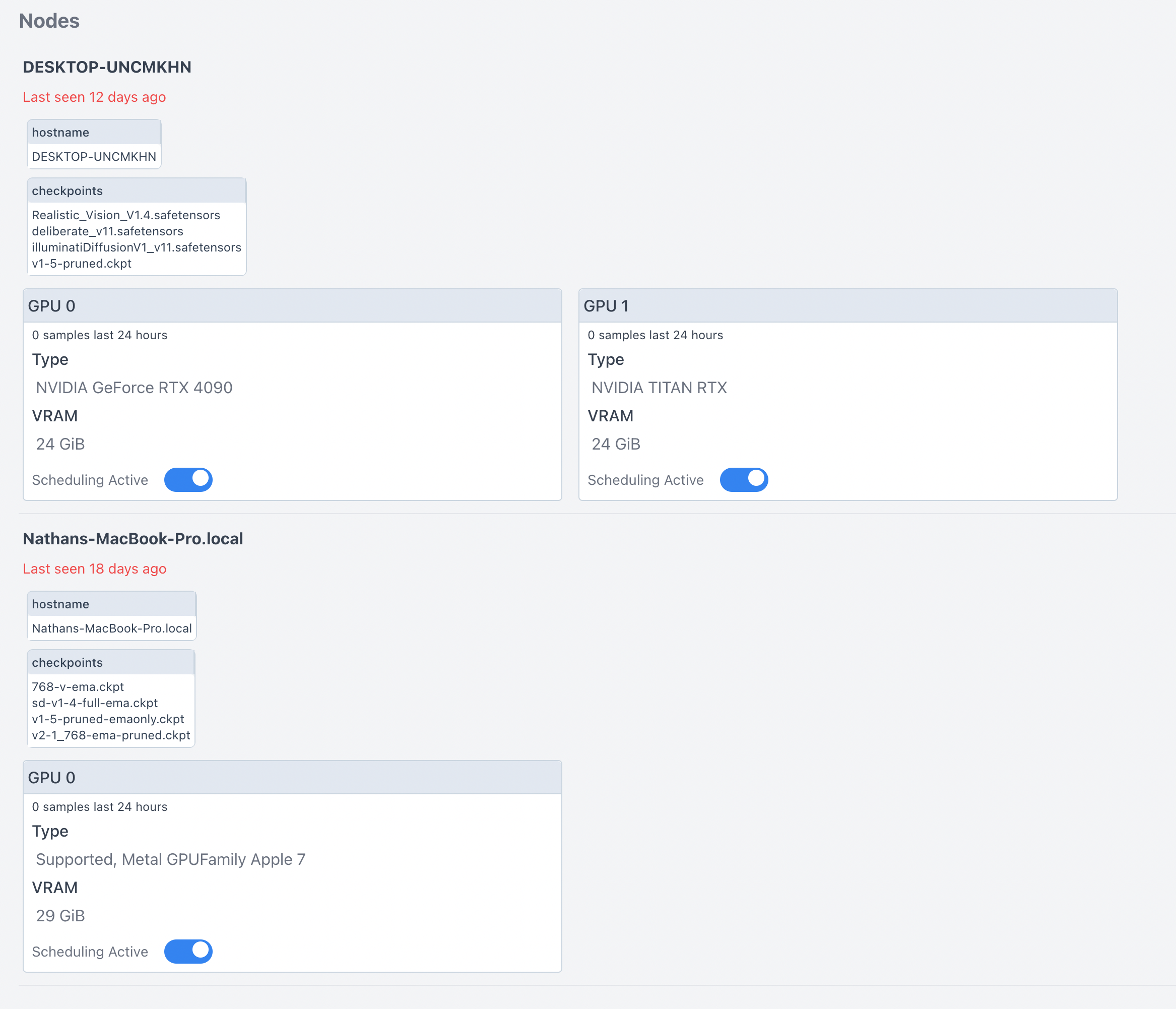

It simply assumes that the local node has Python based HTTP service(s) that fulfill a contract of being able to run inference of various types. The agent only requests the promised jobs, manages their status (e.g., cancelling if they time out), and sends node information back to the coordination server. This information is useful for determining node availability and labeling, such as available checkpoints, models, and LoRas.

The central orchestration server decides how to schedule tasks based on previously received information. This approach is beneficial because it allows you to batch tasks on the fly, interrupt them if necessary (for example, if an image with too high dimensions is created, it can run way over the allotted time), and throw a lot of tasks into a pile to let the scheduler figure out the best order. This efficient use of resources ensures that less important tasks can wait until the more urgent ones are sorted out.

So yea. Suddenly your GPU’s fans are gonna be blasting a lot. I hope you have good cooling.

If needed, scheduling can be paused by toggling a boolean for the node on the server. If too many nodes go offline, there is no need to look at a backed up queue and divine why your queue throughput is decreasing (such as if someone tripped on a cable in a data center), it’s obvious. Their last seen value will be obviously timing out and the server won’t try to schedule there. Likewise, if you have a powerful computer and a less powerful one connected, you can avoid routing tasks that would overload the less powerful one with too much VRAM or take too long to complete.

To simplify my prototype, I used sqlite3 instead of etcd. Although not always scalable, the basic idea is promising. The clients are stateless, which makes them simple but can cause unexpected results. Sometimes they modify incoming requests to avoid these issues, although I’m not sure if that’s actually a smart or a dumb idea yet. For example, they can pick a default model for rendering images, or set default parameters for embeddings. They note these changes in the alloc def sent back with the finished sample(s) so the server can be aware of the change.

The automatic111, i.e. the Python code, currently avoids running concurrent jobs so the GPU doesn’t contend. The scheduling decisions and multiplexing of what gets loaded into GPU memory is not my area of expertise, so I hope people can provide insight on the future of what might we might be able to tighten up there.

Yea but Let’s See a Lil Code

Below are some protobuf sketches of what I’ve been working on. The core methods are included, and more, such as Interrupt, will be supported at some point.

service Amostra {

// Upstream alloc requester requests an alloc.

rpc RequestAlloc(Alloc) returns (AllocStatus) {}

// Server attempts to schedule an alloc on client

rpc ScheduleClientAllocs(stream AllocStatus) returns (stream Alloc) {}

// Client pushes final samples from allocs to the server

rpc PushFinishedSamples(FinishedSamples) returns (PushInfoResponse) {}

// Client pushes information about its node state to the server

rpc PushNodeInfo(NodeInfo) returns (PushInfoResponse) {}

}

RequestAlloc is the method called by the web app that wants something done. It creates a commitment to take care of that asynchronously, tracked by the Alloc’s ID.

ScheduleClientAllocs is a bidirectional method that uses streaming to communicate between the orchestrator server and the client/worker nodes. The server receives requests to run tasks and pushes back status updates (which could include error information or previews). Then, the results are pushed back using the PushFinishedSamples method.

PushNodeInfo is used for status and telemetry reporting. It provides information about the server’s capabilities, including whether it has an NVIDIA graphics card, the type of card, the amount of VRAM, the last time it was seen, and the checkpoints it supports.

The structs themselves have optional information for various sample types, so they don’t send any more information than needed over the wire, but can handle one type for all samples.

enum AllocType {

Train = 0;

Sample = 1;

}

enum SampleType {

Img2Img = 0;

Txt2Img = 1;

Upscale = 2;

Custom = 3;

Blob = 4;

}

message Img2ImgParams {

optional string mask = 1;

optional string prompt = 2;

// etc...

repeated string init_images = 14;

optional int32 batch_size = 15;

}

message Txt2ImgParams {

optional bool enable_hr = 1;

optional double denoising_strength = 2;

optional int32 first_phase_width = 3;

optional int32 first_phase_height = 4;

optional string prompt = 5;

// blah blah blah

optional string model_checkpoint = 29;

}

message SampleParams {

SampleType sample_type = 1;

optional Txt2ImgParams txt_2_img_params = 2;

optional UpscaleParams upscale_params = 3;

optional CustomParams custom_params = 4;

int64 sample_id = 5;

repeated int64 batch_sample_ids = 6;

optional Img2ImgParams img_2_img_params = 7;

}

message ResourceReservations {

uint64 gpu_vram_bytes = 1;

}

message Alloc {

AllocType type = 1;

string id = 2;

optional SampleParams sample_params = 3;

string hostname = 4;

int32 gpu_num = 5;

optional ResourceReservations resource_reservations = 6;

uint32 priority = 7;

}

message Allocs {

repeated Alloc allocs = 1;

}

message AllocStatus {

bool scheduled = 1;

string message = 2;

int32 estimated_duration_ms = 3;

int64 sample_id = 4;

repeated int64 batch_sample_ids = 5;

}

message FinishedSamples {

repeated FinishedSample samples = 1;

}

message FinishedSample {

int32 duration = 1;

bytes data = 2;

string alloc_id = 3;

SampleParams sample_params = 4;

}

Where to Next

I need to overcome my awkwardness and improve my business skills to successfully launch the Tensorscale app (which wraps this stuff, but I’ve been trying to keep everything modular) in public. My plan is to make the orchestrator component open source to allow others to contribute to a cleanly licensed Python agent that can perform various functions. However, I am seeking feedback and validation on these ideas, since I am not sure if they align with what others are doing. I would also like to collaborate with experts in loading models into GPUs and optimizing their efficiency. Although Nvidia has some new technology that could help, it does not benefit me as a 4090 pleb.

So, if you’re interested, give me a shout and tell me what you think of my ideas.

Until next time, stay sassy Internet.

- Nate

nathan leclaire

nathan leclaire